Susanna Siddell

Guest Reporter

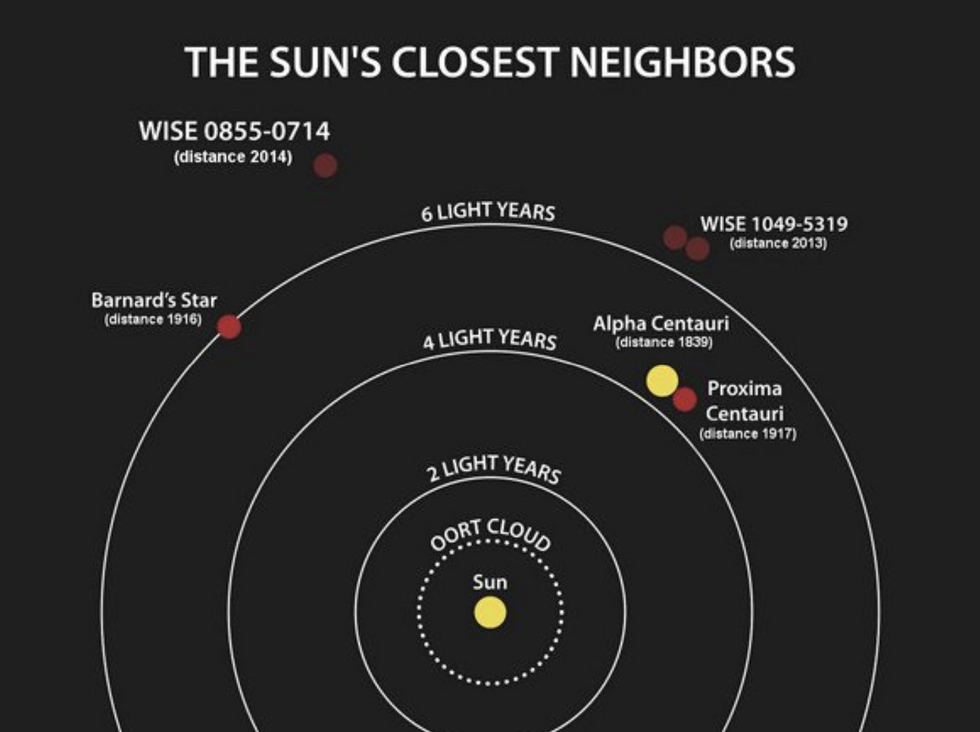

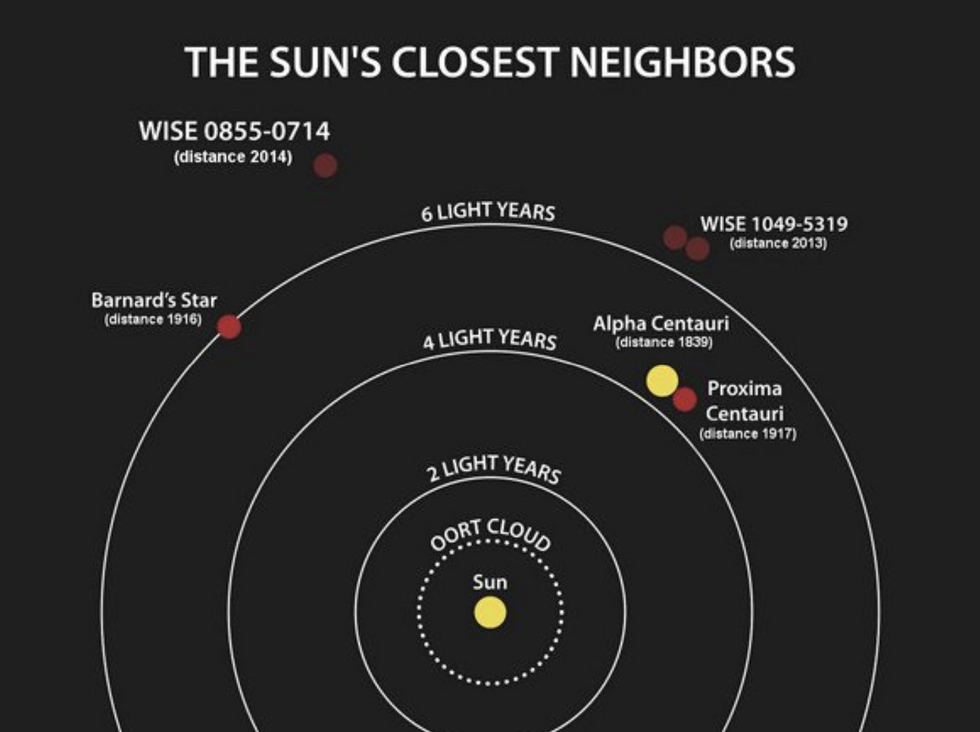

Scientists have just revealed an incredible "breakthrough" discovery of four Earth-like planets orbiting one of our closest stellar neighbours, Barnard's Star.

This exciting revelation is rewriting what is currently known about Earth's galactic neighbourhood and transform how experts search for planets beyond the solar system.

"It's a really exciting find. Barnard's Star is our cosmic neighbour, and yet we know so little about it," said Ritvik Basant, who is a PhD student at the University of Chicago and first author on the study.

The newly detected planets - which have not yet been named - orbit extremely close to their home star and can complete a full orbit in just days, researchers have said.

All four planets are too close to their host star to sustain liquid water and, therefore, life.

"A key requirement for habitability is the presence of liquid surface water," Basant explained.

"If a planet orbits too close to its star, any water would evaporate. If it's too far, it would freeze."

For more than 100 years, astronomers have tried to understand Barnard's Star, but finding planets around it has proven incredibly difficult.

The breakthrough came thanks to some serious space detective work, including a powerful new tool called MAROON-X, which enabled scientists to spot a tiny but crucial "wobble" in the star's movement - a telltale sign that planets are nearby.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS:

Researchers had previously assumed the star was circled by a gas giant similar to Jupiter but, instead, they discovered this wobbling is caused by the combined force of four smaller worlds.

The findings were independently confirmed in two different studies by different instruments, which has boosted wider confidence in the discovery.

"We observed at different times of night on different days. They're in Chile; we're in Hawaii. Our teams didn't coordinate with each other at all," Basant said.

"That gives us a lot of assurance that these aren't phantoms in the data."

This dual confirmation from separate locations and teams provides strong evidence that the planets truly exist.

Lead author Professor Jacob Bean, who works at the University of Chicago, described the discovery as "incredible".

"We worked on this data really intensely at the end of December, and I was thinking about it all the time," Bean said. "It was like, suddenly we know something that no one else does about the universe."

"We found something that humanity will hopefully know forever. That sense of discovery is incredible," he added.

Find Out More...

This exciting revelation is rewriting what is currently known about Earth's galactic neighbourhood and transform how experts search for planets beyond the solar system.

"It's a really exciting find. Barnard's Star is our cosmic neighbour, and yet we know so little about it," said Ritvik Basant, who is a PhD student at the University of Chicago and first author on the study.

The newly detected planets - which have not yet been named - orbit extremely close to their home star and can complete a full orbit in just days, researchers have said.

All four planets are too close to their host star to sustain liquid water and, therefore, life.

"A key requirement for habitability is the presence of liquid surface water," Basant explained.

"If a planet orbits too close to its star, any water would evaporate. If it's too far, it would freeze."

For more than 100 years, astronomers have tried to understand Barnard's Star, but finding planets around it has proven incredibly difficult.

The breakthrough came thanks to some serious space detective work, including a powerful new tool called MAROON-X, which enabled scientists to spot a tiny but crucial "wobble" in the star's movement - a telltale sign that planets are nearby.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS:

- Asteroid 'size of Egypt's Great Pyramid of Giza' to skim past Earth at 60 times speed of sound

- Mysterious spinning white spiral spotted across UK night sky as Met Office reveal cause

- Rare partial solar eclipse to be visible above UK next week as warning issued to Britons

Researchers had previously assumed the star was circled by a gas giant similar to Jupiter but, instead, they discovered this wobbling is caused by the combined force of four smaller worlds.

The findings were independently confirmed in two different studies by different instruments, which has boosted wider confidence in the discovery.

"We observed at different times of night on different days. They're in Chile; we're in Hawaii. Our teams didn't coordinate with each other at all," Basant said.

"That gives us a lot of assurance that these aren't phantoms in the data."

This dual confirmation from separate locations and teams provides strong evidence that the planets truly exist.

Lead author Professor Jacob Bean, who works at the University of Chicago, described the discovery as "incredible".

"We worked on this data really intensely at the end of December, and I was thinking about it all the time," Bean said. "It was like, suddenly we know something that no one else does about the universe."

"We found something that humanity will hopefully know forever. That sense of discovery is incredible," he added.

Find Out More...