Oliver Trapnell

Guest Reporter

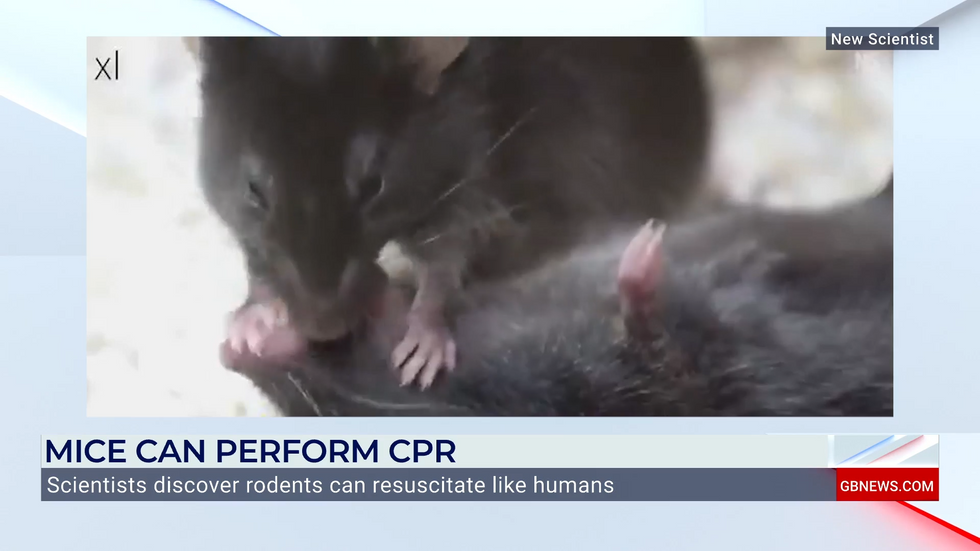

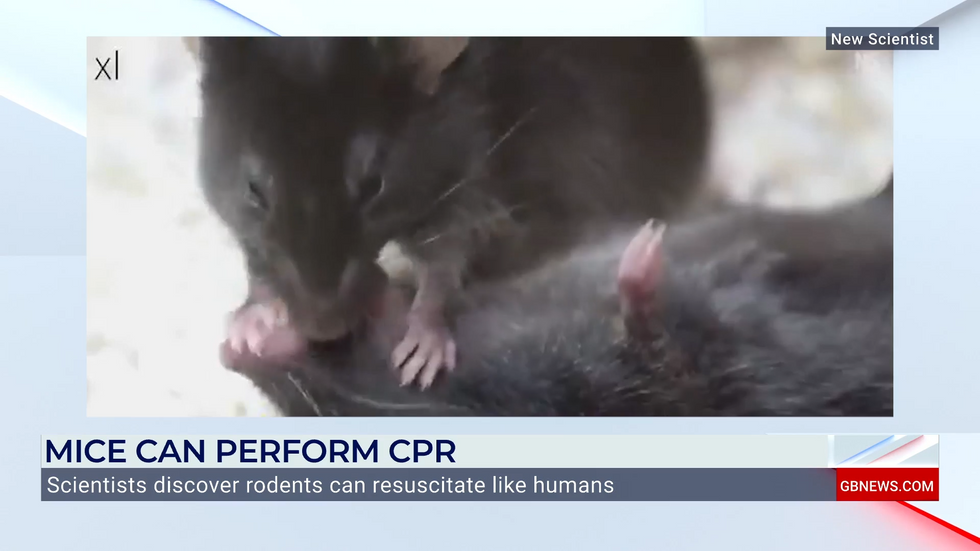

Mice have been observed attempting "first aid" on unconscious companions in groundbreaking new research.

Scientists from the University of Southern California filmed rodents exhibiting remarkable caring behaviours towards drugged, immobilised mice.

The conscious mice tried to clear the airways of their fallen lab-mates by pulling their tongues and biting their mouths in apparent attempts at revival.

They also engaged in unusually intense licking and grooming of the unresponsive animals.

Researchers noted these actions closely resemble human emergency responses.

In the experiment, researchers deliberately drugged mice to immobilise them before placing the unconscious rodents near fully conscious mice.

Scientists observed how the alert mice would react to their incapacitated companions.

Conscious mice displayed a consistent set of behaviours when encountering their unresponsive partners.

These actions escalated from initial sniffing and grooming to more forceful interventions.

The helping behaviours began after prolonged immobility of the partner and stopped once the drugged mouse regained activity.

MORE SCIENTIFIC BREAKTHROUGHS:

The conscious mice were observed pulling tongues out of the way and biting mouths to help their companions breathe.

These actions appeared to be deliberate attempts to clear airways.

Researchers noted the behaviours had practical consequences, including "clearance of foreign objects from the mouth" and "improved airway opening".

The helping actions also appeared to hasten recovery of the drugged mice.

Scientists described these behaviours as "reviving-like efforts" that closely mirror human emergency responses.

The caring actions were rarely seen when partners were merely sleeping or active and marks the first time such caring responses have been documented in mice.

Previous research has found similar behaviours in elephants, chimpanzees and dolphins, which can recognise when an individual is incapacitated.

These larger mammals respond with grooming and nudging of distressed companions.

William Sheeran and Zoe Donaldson from the University of Colorado Boulder noted that "animals as diverse as elephants, chimpanzees and dolphins can recognise and intervene by touching, nudging, and even carrying an incapacitated individual".

The mouse study adds to growing evidence that rescue instincts cross species boundaries.

The study also found mice spent more time trying to revive companions they had previously met and devoted less attention to helping strangers.

Researchers said this difference "suggested social recognition" played a role in their response.

The reviving behaviour was also observed when mice interacted with dead companions.

This suggests the helping instinct is triggered specifically by unresponsiveness, not merely by sleep or normal activity.

The findings indicate a sophisticated level of social awareness in these small rodents.

When researchers studied the mice's brains, they found that encountering a fallen comrade triggered neurons in the paraventricular nucleus.

This activation released oxytocin hormones responsible for social bonding.

The scientists then conducted further tests by blocking the oxytocin activation which significantly impaired the helping behaviours.

Lead author Huizhong Whit Tao wrote in the journal Science: "They displayed distinct and consistent behaviours toward the partner, escalating from sniffing and grooming to more forceful actions such as biting the partner's mouth or tongue and pulling its tongue out."

Tao noted these behaviours emerged specifically "after prolonged immobility and unresponsiveness of the partner and ceased once the partner regained activity".

The researchers concluded: "Our findings thus suggest that animals exhibit reviving-like emergency responses and that assisting unresponsive group members may be an innate behaviour widely present among social animals."

They added that such behaviour "likely plays a role in enhancing group cohesion and survival".

Find Out More...

Scientists from the University of Southern California filmed rodents exhibiting remarkable caring behaviours towards drugged, immobilised mice.

The conscious mice tried to clear the airways of their fallen lab-mates by pulling their tongues and biting their mouths in apparent attempts at revival.

They also engaged in unusually intense licking and grooming of the unresponsive animals.

Researchers noted these actions closely resemble human emergency responses.

In the experiment, researchers deliberately drugged mice to immobilise them before placing the unconscious rodents near fully conscious mice.

Scientists observed how the alert mice would react to their incapacitated companions.

Conscious mice displayed a consistent set of behaviours when encountering their unresponsive partners.

These actions escalated from initial sniffing and grooming to more forceful interventions.

The helping behaviours began after prolonged immobility of the partner and stopped once the drugged mouse regained activity.

MORE SCIENTIFIC BREAKTHROUGHS:

- Scientists discover bizarre cause of death for Mount Vesuvius victims

- Chinese Rover finds evidence of beaches on Mars

- Burning birthday cake candles can impair brain function, scientists warn

The conscious mice were observed pulling tongues out of the way and biting mouths to help their companions breathe.

These actions appeared to be deliberate attempts to clear airways.

Researchers noted the behaviours had practical consequences, including "clearance of foreign objects from the mouth" and "improved airway opening".

The helping actions also appeared to hasten recovery of the drugged mice.

Scientists described these behaviours as "reviving-like efforts" that closely mirror human emergency responses.

The caring actions were rarely seen when partners were merely sleeping or active and marks the first time such caring responses have been documented in mice.

Previous research has found similar behaviours in elephants, chimpanzees and dolphins, which can recognise when an individual is incapacitated.

These larger mammals respond with grooming and nudging of distressed companions.

William Sheeran and Zoe Donaldson from the University of Colorado Boulder noted that "animals as diverse as elephants, chimpanzees and dolphins can recognise and intervene by touching, nudging, and even carrying an incapacitated individual".

The mouse study adds to growing evidence that rescue instincts cross species boundaries.

The study also found mice spent more time trying to revive companions they had previously met and devoted less attention to helping strangers.

Researchers said this difference "suggested social recognition" played a role in their response.

The reviving behaviour was also observed when mice interacted with dead companions.

This suggests the helping instinct is triggered specifically by unresponsiveness, not merely by sleep or normal activity.

The findings indicate a sophisticated level of social awareness in these small rodents.

When researchers studied the mice's brains, they found that encountering a fallen comrade triggered neurons in the paraventricular nucleus.

This activation released oxytocin hormones responsible for social bonding.

The scientists then conducted further tests by blocking the oxytocin activation which significantly impaired the helping behaviours.

Lead author Huizhong Whit Tao wrote in the journal Science: "They displayed distinct and consistent behaviours toward the partner, escalating from sniffing and grooming to more forceful actions such as biting the partner's mouth or tongue and pulling its tongue out."

Tao noted these behaviours emerged specifically "after prolonged immobility and unresponsiveness of the partner and ceased once the partner regained activity".

The researchers concluded: "Our findings thus suggest that animals exhibit reviving-like emergency responses and that assisting unresponsive group members may be an innate behaviour widely present among social animals."

They added that such behaviour "likely plays a role in enhancing group cohesion and survival".

Find Out More...